- Français

- |

- Booklist

- |

- Week of Prayer

- |

- Links

- Areopagus - a forum for dialogue

- Academic journals

- Acronyms

- Bible tools

- Bibliographies

- Booksellers and publishers

- Churches

- Canadian church headquarters

- Directory of Saskatchewan churches

- Retreat centres

- Saskatchewan church and non-profit agencies

- Ecumenism.net Denominational links

- Anabaptist & Mennonite

- Anglican

- Baptist

- Evangelical

- Independent episcopal

- Lutheran

- Methodist, Wesleyan, and Holiness

- Miscellaneous

- Mormon

- Orthodox (Eastern & Oriental)

- Para-church ministries

- Pentecostal / charismatic

- Presbyterian & Reformed

- Quaker (Society of Friends)

- Roman & Eastern Catholic

- United and uniting

- Documents of Ecumenical Interest

- Ecumenical agencies

- Ecumenical Booklist

- Ecumenical Dialogues

- Glossary

- Human rights

- Inter-religious links

- Justice & peace

- Lectionaries

- Religious news services

- Resource pages

- Search Ecumenism.Net

- |

- Documents

- Ancient & Medieval texts

- Ecumenical Dialogues

- Interreligious

- Anabaptist & Mennonite

- Anglican

- Evangelical

- Lutheran

- Orthodox

- Reformed & Presbyterian

- Roman & Eastern Catholic

- United & Uniting

- Miscellaneous churches

- Canadian Council of Churches (CCC)

- Conference of European Churches (CEC)

- Interchurch Families International Network (IFIN)

- National Council of Churches in Australia (NCCA)

- Lausanne Committee for World Evangelism (LCWE)

- World Council of Churches (WCC)

- Other ecumenical documents

Church traditions

Documents from ecumenical agencies

- |

- Dialogues

- Adventist-Reformed

- African Instituted Churches-Reformed

- Anglican-Lutheran

- Anglican-Orthodox

- Anglican-Reformed

- Anglican-Roman Catholic

- Anglican-United/Uniting

- Baptist-Reformed

- Disciples of Christ-Reformed

- Disciples of Christ-Roman Catholic

- Evangelical-Roman Catholic

- Lutheran-Mennonite

- Lutheran-Mennonite-Roman Catholic

- Lutheran-Reformed

- Lutheran-Roman Catholic

- Mennonite-Reformed

- Mennonite-Roman Catholic

- Methodist-Reformed

- Methodist-Roman Catholic

- Oriental Orthodox-Reformed

- Orthodox-Reformed

- Orthodox-Roman Catholic

- Pentecostal-Reformed

- Prague Consultations

- REC-WARC Consultations

- Roman Catholic-Lutheran-Reformed

- Roman Catholic-Reformed

- Roman Catholic-United Church of Canada

- |

- Quick links

- Canadian Centre for Ecumenism

- Canadian Council of Churches

- Ecumenical Shared Ministries

- Ecumenism in Canada

- Interchurch Families International Network

- International Anglican-Roman Catholic Commission for Unity and Mission

- Kairos: Canadian Ecumenical Justice Initiatives

- North American Academy of Ecumenists

- Prairie Centre for Ecumenism

- Réseau œcuménique justice et paix

- Week of Prayer for Christian Unity

- Women's Interchurch Council of Canada

- World Council of Churches

- |

- Archives

- |

- About us

Scholars outline history of the Pharisees and roots of harmful anti-Jewish stereotypes

— Nov. 19, 202219 nov. 2022Every religion has its demonology. When Malcolm X made this observation to Alex Haley as they collaborated on what was to become his posthumous autobiography, his immediate target was the antisemitic teaching promoted by Elijah Muhammed, from whose sect he had recently broken. His refusal to exempt any faith from the tendency to demonize others in order to validate itself remains as painfully relevant today as it was in 1965.

- The Pharisees

Joseph Sievers and Amy-Jill Levine, eds

Eerdmans, 2021

ISBN: 978-0-8028-7929-5

A mere eight months after Malcolm X’s assassination, the Catholic Church promulgated Nostra Aetate, repudiating two millennia of Christian demonization of Jews and Judaism. The main focus of that declaration was replacement theology (the claim that the church had replaced Israel as God’s covenant people) and its justifying myth of the blood libel (the claim that the entire Jewish people were and are uniquely responsible for the death of Jesus). As the task of implementing Nostra Aetate got underway, it became evident that absolving Jews of deicide was only the tip of an iceberg of vilification that would need to be dismantled if the church were to free itself from antisemitism.

In 1974, the Pontifical Commission for Religious Relations with the Jews flagged problematic portrayals of the Pharisees as an urgent topic. Subsequent curial documents repeated the call for an historically balanced appraisal of the Pharisees. In 2019, marking the 110th anniversary of its founding, Rome’s Pontifical Biblical Institute hosted an international conference to consider what we know — and do not know — about the Pharisees, their place in the Jewish and Christian imagination, and the damaging effects of reproducing erroneous notions about them in contemporary Christian preaching and teaching. With the publication of the proceedings of this conference in a volume titled The Pharisees, we now have a powerful resource for countering these harmful misconceptions.

Read this complete review in the National Catholic Reporter

Most Catholics, unless they identify with a retrograde fringe group, are unlikely to regard Jews as especially hypocritical, legalistic, xenophobic, misogynistic or complicit in whatever other ill they deplore. With the recent resurgence of antisemitic violence, the validity of this assumption may be eroding. Still, most North American Catholics would probably not think of themselves as anti-Jewish, much less antisemitic. This is testimony to the rhetorical success of Nostra Aetate.

So far as we know, the Pharisaic sect did not survive the first century. Even if elements of their philosophy and practice were absorbed into the rabbinic movement that eventually became the mainstream of Judaism, there are no “card-carrying” Pharisees alive today. Why should it matter to the common good what people think and say about them?

Each of the 27 contributors to this collection explores a different facet of this question. Susannah Heschel and Deborah Forger put it most succinctly: In the Christian mind, Pharisees have become a “metonym” for Judaism; that is, whatever is said about the Pharisees Christians assume to be true — or at least typical — of all Jews. When this assumption is combined with Christian ignorance of actual Jews and Judaism, anything, however false or misleading, is more readily believed. To the extent that Christian stereotypes of Jews become intimately bound up with Christian self-understanding, attempts at correction may be perceived as a challenge to Christianity itself and tend to be met with knee-jerk deflection or denial. Rather than confront uncomfortable truths, Christians prefer the comforting reassurances of their own echo chamber. Amy-Jill Levine, one of the volume’s editors, instructively compares this to the dynamic of white privilege and white fragility: Like racism, Jew-hatred persists because Christians continue to enable it, if not through direct preaching and teaching then through inaction.

How did the Pharisees become Judaism’s demonic essence in Christian eyes? As several of the contributors document, the process began with the Gospels, which regularly use the Pharisees as negative foils for Jesus and his followers. Sometimes the evangelists anchor this unflattering contrast in disagreements over historically specific practices; on other occasions, the Pharisees’ antagonism is left unexplained or is ahistorically lumped together with that of other unrelated groups.

As the demographic balance of the early church shifted from Jews to gentiles, the evangelists, writing exclusively or predominantly for non-Jews, could repurpose these intramural disputes in the service of a generalized portrait of Jewish badness, a polemic that reaches its apogee in John’s Gospel, where Pharisees — now virtually interchangeable with “the Jews” — exemplify the cosmic darkness over against which the illumination of the incarnate Word is juxtaposed.

This polemic was not entirely successful. Matthew’s Jesus identifies the righteousness of the Pharisees as the high bar which his own followers must surpass in order to achieve perfection. (Note: It is Jesus, not the Pharisees, who demands perfection; it is Jesus, not the Pharisees, who makes the practice of Torah more rigorous.) Later in the same Gospel, Jesus launches into a virulent indictment of Pharisaic hypocrisy while insisting that his own disciples adhere to Pharisaic norms — implying that the norms themselves are good. Luke portrays the Pharisees as hospitable and solicitous toward Jesus despite his criticisms. Even John imagines the possibility of a Pharisaic sympathizer in Nicodemus.

The premise of an “us-versus-Pharisees” dichotomy is further undermined by the Book of Acts, where Pharisees appear as both members and allies of the nascent church. Paul definitively discredits the smear campaign by trumpeting his Pharisaic credentials in the present tense. Although Christians have often sought to explain away his self-identification as a Pharisee as ironic, Paula Fredriksen makes a convincing case that Paul means what he says. (Paul’s theology of grace and election, his pastoral sensitivity and his method of biblical interpretation owe much to his Pharisaic training.)

But if the connections between the Pharisees and Christian origins are complex, the fate of the Pharisees within developed Christian discourse is far more univocal and negative. As Fr. Luca Angelelli demonstrates, the very adjective “Pharisaic” is a pejorative Christian invention. As early as the second century, Benedictine Fr. Matthias Skeb shows that the Pharisees were identified as a source of Christian heresies. And with the advent of the Reformation, Randall Zachman details how playing the Pharisee card became a potent weapon for Luther and Calvin to attack the Catholic hierarchy — inadvertently prompting the erroneous implication that the Pharisees of Jesus’ day were in charge of things.

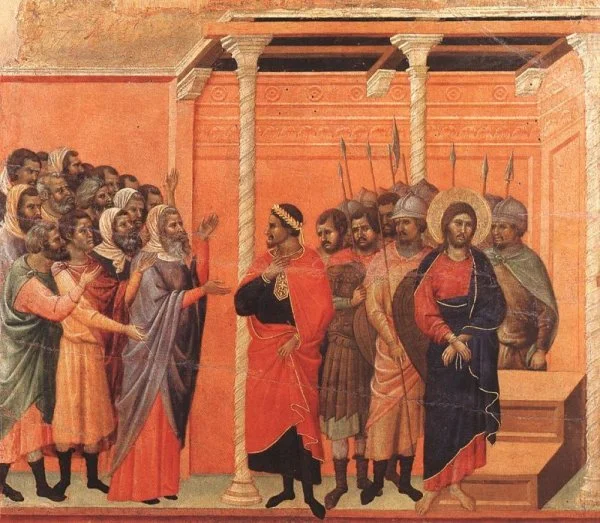

This verbal demonization received reinforcement in Christian art during the Middle Ages. Angela La Delfa‘s essay notes that the Fourth Lateran Council‘s mandate that Jews wear distinctive garb in public cemented the visual equation of Pharisees with all Jews. Christian Stückl‘s guide to the history of the Oberammergau Passion play likewise illustrates how ordinary Christians freely amplified the Pharisees’ involvement in Jesus’ death (Pharisees are largely absent from the Gospel Passion narratives) and, in some Passion plays, even named these fictional villains after their modern Bavarian Jewish neighbors. When Hitler attended the Oberammergau play in 1934, he declared it “of significance for the Reich.” Holocaust scholars have long recognized that while Christianity did not cause the Shoah, its demonology helped make it possible.

In contrast to Christianity’s enduring obsession with them, Pharisees played a decidedly marginal role within Jewish tradition before the modern era — at least by name. That they were a significant movement within pre-70 A.D. Judaism is confirmed by the Jewish historian Josephus, and it is likely that the Dead Sea Scrolls sect alluded to them.

However, as several of the volume’s contributors point out, the Mishnah, the earliest compilation of rabbinic tradition, omits the Pharisees from the chain of succession upon which the rabbis based their legitimacy. According to Shaye Cohen, it is not until the 10th century that an anonymous Jewish author retroactively equated the Pharisees with the founders of rabbinic Judaism. The proposal seems not to have gained much traction at the time. Elsewhere, whenever medieval Jewish writings mention parush (the Hebrew word that stands behind the transliteration “Pharisee”), they refer to contemporary pious individuals who pursue God’s call to holiness with integrity — not to members of a long-forgotten sect.

Given this millennial obsolescence of the Pharisees within Judaism, how did they become such a virulent flashpoint in modern Jewish-Christian relations? The watershed can be pinpointed to the year 1875, when Abraham Geiger, a German-born rabbi, published a controversial book arguing that the Pharisees were, in fact, the spiritual progenitors of the Reform Judaism Geiger himself advocated. In Heschel and Forger’s summary, Geiger portrayed the Pharisees as “the liberalizing, progressive movement that … sought to democratize Judaism by making each Jew equal to a priest and each home equal to a temple.” Shades of Luther’s “priesthood of all believers.” Geiger went still further, contending that Jesus was himself a Pharisee, a fact suppressed by the Gospels. Judaism and Christianity (rightly understood) were thus not so different after all.

Geiger was a competent scholar, not an ideologue, but his thesis was transparently shaped by the ideological circumstances of 19th century Europe. The emerging secular nation-states had only recently emancipated the Jews from forced ghettoization. Jews now had to negotiate their new political identity as citizens within a still Christian-dominated culture. Jews had to make the case that they belonged; challenging Christianity’s myth of a Jesus totally divorced from Judaism — antithetically epitomized by the Pharisees — was a survival strategy.

Nor was it only ecclesiastical tradition that had to be countered; the 19th century also saw the mutation of theological anti-Judaism into a racial antisemitism that promoted an Aryan Jesus, genetically as well as spiritually purified of Jewish taint. Geiger’s apologetic was oversimplified (as all apologetics are), but it exposed the cracks in the traditional narrative. Resistance was fierce and protracted, but in the long run, Geiger’s challenge created space for a more authentic recovery of Jewish and Christian origins.

So, what do we know about the historical Pharisees? The cautious refrain of the contributors to this volume is, “Not much.” No self-identified Pharisee (except Paul) has left anything in writing for us to go on; no source — Josephus, the Dead Sea Scrolls, the New Testament, the Mishnah — offers a comprehensive account of their beliefs, values and practices.

But we are not left entirely in the dark. We know they were a small lay movement (Josephus numbers them at 6,000 during the reign of Herod the Great) who were committed to interpreting and living out God’s commandments for Israel — a commitment which won them the approval of the common people. They were prepared to challenge secular authority; they also supported popular religious practice. They believed in the cooperation of free will and divine grace, and in the resurrection of the dead.

The purported alignment of the Pharisees with the values of the masses makes it difficult to assess how many of the priorities attributed to them were distinctive. Eric Meyers, for example, notes that the archaeology of Galilee reveals a widespread interest in everyday ritual purity that reflects what we know about Pharisaic practice but which was surely not limited to them. This supports Geiger’s basic impulse to see the Pharisees as embodying a Jewish mainstream that contributed to the post-70 A.D. rabbinic movement. Conversely, to the extent that the controversies between the Pharisees and Jesus are indeed historical and are not simply proxies for later Christian polemics, Yair Furstenberg argues that Jesus seems to align himself with priestly rather than popular viewpoints. Even with the limited evidence available, there is much to be learned here.

The conference that produced this volume was notable for its ecumenical and interreligious inclusivity. The contributing scholars were Jews and Christians, Protestants and Catholics, women and men, priests and laity. This diversity of affiliation and expertise models the kind of collaboration needed not only to advance knowledge but also to bring that knowledge to bear on an ongoing problem: the (often unintentional) perpetuation of misinformation about Jews by Christians at the pulpit, in the classroom and in cultural discourse generally.

The urgency of this problem was underscored by Pope Francis, who addressed the conference participants at a special audience. In his remarks, the Holy Father echoed the main conclusion of the conference:

The history of interpretation has fostered a negative image of the Pharisees, often without a concrete basis in the Gospel accounts. And often, over time, this view has been attributed by Christians to Jews in general. In our world, such negative stereotypes have unfortunately become very common. One of the oldest and most damaging stereotypes is precisely that of “Pharisee,” especially when used to put Jews in a negative light. … [T]o love our neighbours better, we need to know them, and to know who they are we often have to find ways to overcome ancient prejudices.

This book is an important first step in this process.

Permanent link: ecumenism.net/?p=12825

Permanent link: ecumenism.net/?p=12825

Categories: NCR, Opinion • In this article: anti-semitism, Jewish-Christian relations

Lien permanente : ecumenism.net/?p=12825

Lien permanente : ecumenism.net/?p=12825

Catégorie : NCR, Opinion • Dans cet article : anti-semitism, Jewish-Christian relations