- Français

- |

- Booklist

- |

- Week of Prayer

- |

- Links

- Areopagus - a forum for dialogue

- Academic journals

- Acronyms

- Bible tools

- Bibliographies

- Booksellers and publishers

- Churches

- Canadian church headquarters

- Directory of Saskatchewan churches

- Retreat centres

- Saskatchewan church and non-profit agencies

- Ecumenism.net Denominational links

- Anabaptist & Mennonite

- Anglican

- Baptist

- Evangelical

- Independent episcopal

- Lutheran

- Methodist, Wesleyan, and Holiness

- Miscellaneous

- Mormon

- Orthodox (Eastern & Oriental)

- Para-church ministries

- Pentecostal / charismatic

- Presbyterian & Reformed

- Quaker (Society of Friends)

- Roman & Eastern Catholic

- United and uniting

- Documents of Ecumenical Interest

- Ecumenical agencies

- Ecumenical Booklist

- Ecumenical Dialogues

- Glossary

- Human rights

- Inter-religious links

- Justice & peace

- Lectionaries

- Religious news services

- Resource pages

- Search Ecumenism.Net

- |

- Documents

- Ancient & Medieval texts

- Ecumenical Dialogues

- Interreligious

- Anabaptist & Mennonite

- Anglican

- Evangelical

- Lutheran

- Orthodox

- Reformed & Presbyterian

- Roman & Eastern Catholic

- United & Uniting

- Miscellaneous churches

- Canadian Council of Churches (CCC)

- Conference of European Churches (CEC)

- Interchurch Families International Network (IFIN)

- National Council of Churches in Australia (NCCA)

- Lausanne Committee for World Evangelism (LCWE)

- World Council of Churches (WCC)

- Other ecumenical documents

Church traditions

Documents from ecumenical agencies

- |

- Dialogues

- Adventist-Reformed

- African Instituted Churches-Reformed

- Anglican-Lutheran

- Anglican-Orthodox

- Anglican-Reformed

- Anglican-Roman Catholic

- Anglican-United/Uniting

- Baptist-Reformed

- Disciples of Christ-Reformed

- Disciples of Christ-Roman Catholic

- Evangelical-Roman Catholic

- Lutheran-Mennonite

- Lutheran-Mennonite-Roman Catholic

- Lutheran-Reformed

- Lutheran-Roman Catholic

- Mennonite-Reformed

- Mennonite-Roman Catholic

- Methodist-Reformed

- Methodist-Roman Catholic

- Oriental Orthodox-Reformed

- Orthodox-Reformed

- Orthodox-Roman Catholic

- Pentecostal-Reformed

- Prague Consultations

- REC-WARC Consultations

- Roman Catholic-Lutheran-Reformed

- Roman Catholic-Reformed

- Roman Catholic-United Church of Canada

- |

- Quick links

- Canadian Centre for Ecumenism

- Canadian Council of Churches

- Ecumenical Shared Ministries

- Ecumenism in Canada

- Interchurch Families International Network

- International Anglican-Roman Catholic Commission for Unity and Mission

- Kairos: Canadian Ecumenical Justice Initiatives

- North American Academy of Ecumenists

- Prairie Centre for Ecumenism

- Réseau œcuménique justice et paix

- Week of Prayer for Christian Unity

- Women's Interchurch Council of Canada

- World Council of Churches

- |

- Archives

- |

- About us

Baptism, Footwashing, and Mission | One Body

What if footwashing were a sacrament? Of all of the things that Jesus instructed the disciples to do, why didn’t footwashing become a sacrament like the others? Thoughts like these are one of the hazards of being a theologian.

I was thinking about this strange idea this week while reflecting on Pope Leo XIV’s new series of catecheses on Vatican II. Just when he is encouraging us to re-read the documents of the Council, the CCCB has issued a new National Strategy on Ecumenism. The first step in this strategy is to focus on education and formation about the church’s ecumenical teaching, beginning with the Council.

Catholic ecumenical principles start from the understanding that we share a common baptism with other Christians. This was the heart of the Council’s teaching in Lumen Gentium (Dogmatic Constitution on the Church) and Unitatis Redintegratio (Decree on Ecumenism). Although footwashing and baptism are both signs of washing, their broader meanings are different. As a visible sign of grace, baptism effects what it depicts: we are washed of sin and incorporated into the Body of Christ and into his mission. What is depicted in footwashing? The significance of footwashing becomes clearer when we consider its Latin name, mandatum, literally a mandate or commissioning.

Read the rest of this article in the One Body blog on Salt+Light Media

Footwashing is found in the Gospel of John 13:1-17, during the Last Supper. Appearing only in John’s account and not those of Matthew, Mark, or Luke, the footwashing replaces the eucharistic Words of Institution found in the synoptic accounts, so it was clearly a matter of importance to John. Jesus gets up from the table, takes off his outer robe, wraps a towel around himself, pours water into a basin, and begins to wash the disciples’ feet. We see this enacted during the Holy Thursday liturgy with priests and bishops washing the feet of parishioners. For Jesus, this was an inversion of the power structures in first-century Palestine. Footwashing, to remove the dust of the road, was the task of servants, which is why Peter objects to Jesus’ attempt to wash his feet. The dialogue here is instructive: Peter suggests that Jesus wash not just his feet but his hands and head as well, which would not have been a servant’s role. Jesus responds that “One who has bathed does not need to wash, except for the feet, but is entirely clean” (v. 10).

In the second part of this passage, Jesus returns to the table and speaks to all the disciples. He asks them,

Do you know what I have done to you? … So, if I, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also ought to wash one another’s feet. For I have set you an example, that you also should do as I have done to you (v. 12-15).

Here is the mandate or commission: to do for one another what Jesus has done for us. Footwashing thus has become a symbol of diaconal service. The Greek word diakonos means servant or waiter. Throughout Christian history, iconography has depicted deacons washing the feet of the poor.

Interestingly, neither footwashing nor the towel and basin have been incorporated into the Catholic rite for diaconal ordination, and it is the priest, not the deacon, who is to wash feet on Holy Thursday. Several other Western churches, like Anglicans, Lutherans, and Methodists, have restored or renewed the ministry of deacons over the past several decades. As they did, they incorporated various aspects of this symbolism into their rites. The Canadian Anglican-Roman Catholic dialogue has just begun a study of diaconal ministry in our two traditions, which should continue over the next several years.

Let’s return to my initial question, “Why isn’t footwashing a sacrament?” For Catholics, footwashing is a sacramental rite, by which we mean that it is a powerful sign of humility and service, but it is not a primary vehicle through which God’s saving grace is uniquely channelled. The spiritual meaning of footwashing is already contained in the other sacraments, particularly baptism, but also ordination and confession. For some Anabaptist groups, like the Amish, Old Mennonites, and Hutterites, footwashing is one of the three “ordinances,” together with baptism and the Lord’s Supper. Though they don’t speak of “sacraments,” they practice the three ordinances in faithful response to Christ’s command.

In some contexts, footwashing also has a penitential meaning. In 2010, the Lutheran World Federation held its Assembly in Stuttgart, Germany. There, they issued an apology to the Mennonite World Conference for the persecution of Anabaptists during the 16th century. The prayer service included a footwashing where Lutheran delegates washed the feet of visiting Mennonites. They used a pine tub fashioned by an Amish community in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, that had experienced a school shooting in 2006. The tub included a plaque referencing John 13:14: “From this time forward let us serve together our common Lord and Teacher.” The practice of footwashing has become a recurring feature in subsequent Mennonite and Lutheran meetings. It is also a common practice at Bridgefolk, a Catholic-Mennonite dialogue conference.

The mandate to “do for one another what Jesus has done for us” is indeed a baptismal call. In baptism, we are called to engage in Christ’s mission in the world. In baptism, as we are incorporated into Christ’s body, we enter a covenant with Christ and one another to renounce sin, profess our faith, and take up Christ’s cross. Catholic theology understands the church as the continuing presence of Christ in the world. Christ’s mission is our mission.

In 2021, the Roman Catholic-United Church of Canada Dialogue (RC-UCC) issued a report that starts from our common understanding of baptism and calls us to work together in Christ’s mission. Titled “Common Baptism, Common Mission,” the report begins by reminding us of the 1975 agreement in Canada between the so-called PLURA churches (Presbyterian, Lutheran, United, Roman Catholic, and Anglican) on the mutual recognition of baptism celebrated with water and the invocation of the Trinity: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. I served as a member of the recent dialogue, which produced this report about the common ministry that we share. As members of the Body of Christ, we all participate in the Missio Dei, God’s mission in the world.

As our report notes, both the Catholic and the United churches understand the “whole people of God” as a priesthood of all believers (1 Peter 2:5). Though this was a central theme in the 16th century Reformation, it is also affirmed in Vatican II’s Lumen Gentium: “The baptized, by regeneration and the anointing of the Holy Spirit, are consecrated as a spiritual house and a holy priesthood” (#10).

Our churches agree that the sacrament of baptism is the foundation of the vocation and ministry of every Christian. The United Church affirms that: “for the sake of the world God calls all followers of Jesus to Christian ministry. To embody God’s love in the world, the work of the Church requires the ministry and discipleship of all believers” (A Song of Faith, 2006). In Lumen Gentium, the ministry of the people of God is articulated in the following way: “All the faithful of Christ of whatever rank and status are called to the fullness of Christian life and to the perfection of charity…The forms and tasks of life are many, but holiness is one” (#4).

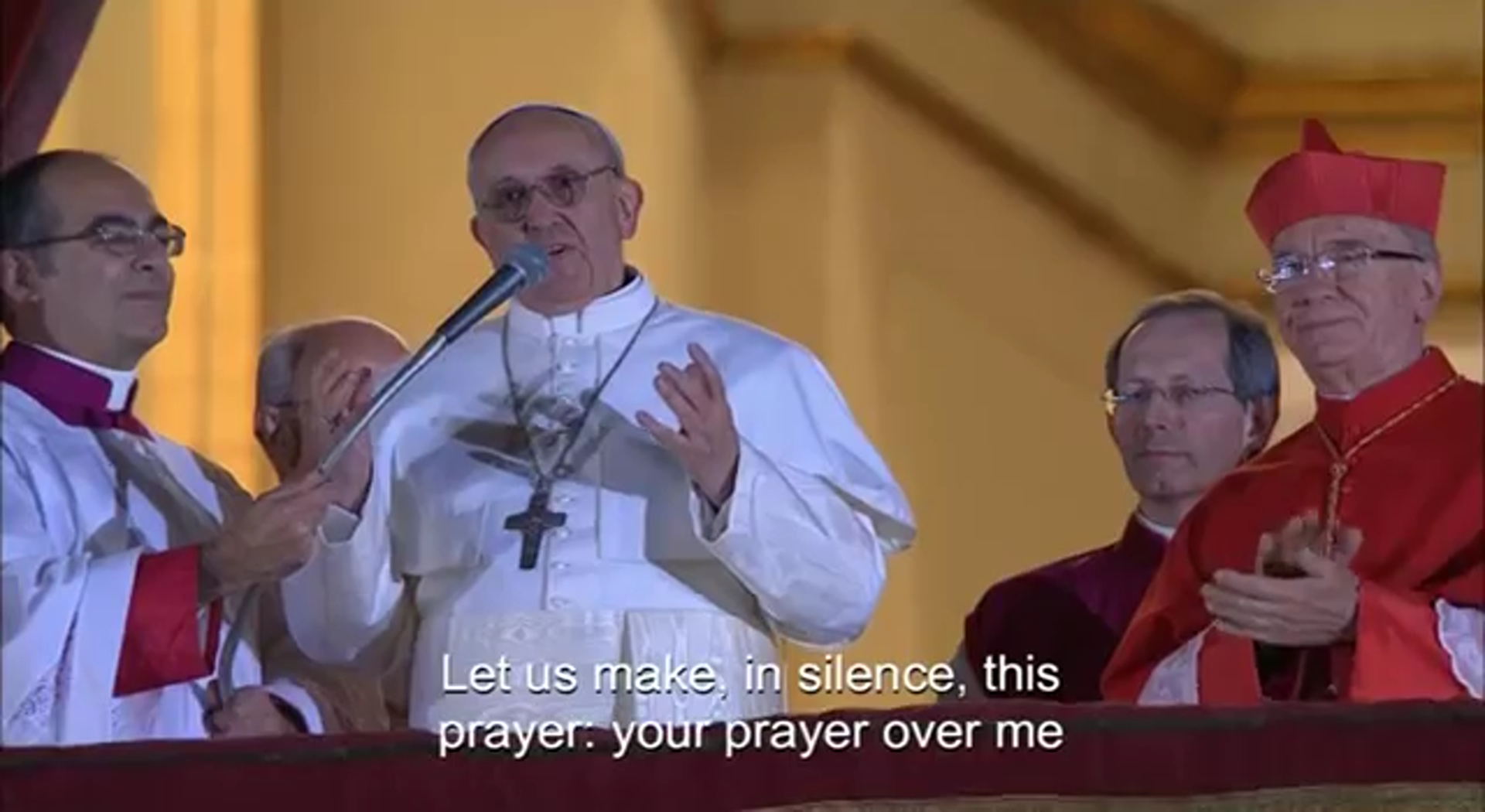

Ministry takes many forms, ordained and lay, yet all the baptized participate in the one, ongoing ministry of Jesus in the world. Though the dialogue report was prepared before Pope Francis brought our attention to synodality, the same theme of the common priesthood of all believers is central to synodal life in the church (see, for example, the Synod on Synodality, Final Document #4).

Early in his papacy, Pope Francis reminded us that Christ ministered to those on the margins. In Evangelii Gaudium, he wrote:

I prefer a Church which is bruised, hurting, and dirty because it has been out on the streets, rather than a Church which is unhealthy from being confined and from clinging to its own security. I do not want a Church concerned with being at the centre and which then ends by being caught up in a web of obsessions and procedures (#49).

Or, as the World Council of Churches reminds us:

Marginalized people are agents of mission and exercise a prophetic role which emphasizes that fullness of life is for all.… In order to commit ourselves to God’s life-giving mission, we have to listen to the voices from the margins to hear what is life-affirming and what is life-destroying. We must turn our direction of mission to the actions that the marginalized are taking (Commission on World Mission and Evangelism, Together Towards Life: Mission and Evangelism in Changing Landscapes, #107).

In calling our churches to minister together among the marginalized, the RC-UCC dialogue affirmed three important dimensions of this common mission:

First, based on our earlier work on climate change and the environment, the dialogue members stressed the need for an ecological conversion. In our previous report, The Hope Within Us (2018), we had already called our churches to recognize “the profound impact of climate change, particularly upon vulnerable peoples and ecosystems” and the need for “a spiritual conversion that gives priority to those on the margins, to those who are most vulnerable in our world.”

Second, recognizing the oneness of Christ among our distinctive identities and ministries, we called for greater awareness and concern for the global church. In the words of Pope Francis, “The challenge, in short, is to ensure a globalization in solidarity, a globalization without marginalization” (Querida Amazonia, #17, quoting St. John Paul II, Message for the 1998 World Day of Peace, #3).

Third, the dialogue called for the inclusion of marginalized groups in the church’s ministry and mission. We wrote:

Our understanding of ministry and leadership within the church must be a model of a society transformed by “intercultural relations where diversity does not mean threat, and does not justify hierarchies of power of some over others, but dialogue between different cultural visions, of celebration, of interrelationship and of revival of hope.” This is a challenging “vision of a diverse justice-seeking–justice-living church engaged in the world for love, justice, and the integrity of creation, transformed from the inside out and from the outside in” (quoting Fifth General Conference of the Latin American and Caribbean Bishops, Aparecida Document, 29 June 2007, #97 and The United Church of Canada, “Towards 2025: A Justice Seeking/Justice-Living Church,” p. 130d).

When we took up the topic of common mission, the RC-UCC dialogue understood that our churches have been ecumenical partners for several decades and that our agreement on a common baptism is now largely taken for granted. We wanted to spur Canadian churches to further ecumenical work together in dialogue and in social justice. “It is the hope of this dialogue that in local ecumenical contexts, mutual recognition of common baptism will mean that local Catholic parishes and United Church faith communities will look to one another as true partners in this ministry to which we are all called as members of the Body of Christ” (Common Baptism, Common Mission, p. 8).

As we begin the season of Lent, I encourage you to reflect on your call to share in Christ’s mission in the world and the ways that you might do this together with other Christians with whom we share a common baptism. On Holy Thursday, when your feet are washed, or you wash another’s feet, imagine if that person were from another Christian community. How might our mandate to “do for others what Christ has done for us” be better understood if we shared this mission with our Christian neighbours?

Nicholas Jesson is the ecumenical officer for the Archdiocese of Regina. He is currently a member of the Anglican-Roman Catholic Dialogue in Canada and of the Canadian Council of Churches’ Commission on Faith & Witness, editor of the Margaret O’Gara Ecumenical Dialogues Collection, and editor of the Anglican-Roman Catholic Dialogue archive IARCCUM.org. He was ecumenical officer for the Diocese of Saskatoon (1994-1999 and 2008-2017), executive director of the Prairie Centre for Ecumenism (1994-1999), and member of the Roman Catholic-United Church of Canada Dialogue (2012-2020).

Permanent link: ecumenism.net/?p=14835

Permanent link: ecumenism.net/?p=14835

Categories: One Body, Opinion • In this article: baptism, diakonia, mission, ordinances, sacraments

Lien permanente : ecumenism.net/?p=14835

Lien permanente : ecumenism.net/?p=14835

Catégorie : One Body, Opinion • Dans cet article : baptism, diakonia, mission, ordinances, sacraments

Ukraine, Canada, and the Church: Calls to action and prayer

— Feb. 24, 202624 févr. 2026

As we approach the fourth anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the twelfth anniversary of its illegal occupation of Crimea and parts of eastern Ukraine, we once again address Canadian Christians with urgency, grief, and hope. These calls to action build on the witness offered in February 2024 when we released A Canadian Pastoral Letter on Ukraine, Canada and the Church. It arises from relationships of shared prayer, co-suffering, and discernment among Ukrainian Orthodox, Ukrainian Catholic, Evangelical, and other Christian leaders, together with the World Evangelical Alliance Peace & Reconciliation Network, The Evangelical Fellowship of Canada, and The Canadian Council of Churches. We write again because the war continues, suffering deepens, and faithful Christian witness remains urgently needed.

… Read more » … lire la suite »

Churches Worldwide to Celebrate Feast of Creation

— Feb. 20, 202620 févr. 2026

A growing ecumenical movement is reshaping church calendars worldwide. The Feast of Creation — celebrated annually on Sept. 1 and also known as Creation Day or the World Day of Prayer for Creation — is being formally added to the liturgical calendars of many churches.

The World Communion of Reformed Churches is supporting the initiative alongside the World Council of Churches, Middle East Council of Churches, Anglican Communion, Lutheran World Federation, and the World Methodist Council.

… Read more » … lire la suite »

Board of Peace a ‘colonialist operation’: Cardinal

— Feb. 18, 202618 févr. 2026

Cardinal Pierbattista Pizzaballa, Latin patriarch of Jerusalem, strongly criticised the U.S.-led Board of Peace, an international body chaired by President Donald Trump to oversee the governance and reconstruction of Gaza. During an event at the Roman parish of San Francesco a Ripa Grande, Pizzaballa was asked by moderator Maria Gianniti, Rome correspondent for the Italian news channel RAI, about his thoughts on the Board of Peace.

“What do I think of the Board of Peace? I think it is a colonialist operation: others deciding for the Palestinians,” Pizzaballa said, according to a report by Italian newspaper Il Sole 24 Ore. The cardinal also commented on the invitation extended to the Vatican to join the international body and its $1-billion price tag for a permanent seat on the board.

… Read more » … lire la suite »

Lutherans and Catholics explore deep ecumenical potential of Augsburg Confession

— Feb. 12, 202612 févr. 2026

Catholic and Lutheran theologians meet in Slovenia to begin drafting a joint statement marking the 500th anniversary of the Augsburg Confession.

The launch of the Sixth Phase of the International Lutheran-Catholic Commission on Unity bears fruit in Slovenia.

“We discerned new perspectives and highlighted the deep ecumenical potential of the Augsburg Confession,” said Prof. Dr Dirk Lange, The Lutheran World Federation (LWF) Assistant General Secretary for Ecumenical Relations, following the launch of a new phase of theological dialogue with the Roman Catholic Church.

… Read more » … lire la suite »

A paradigm shift for English Catholicism

— Feb. 11, 202611 févr. 2026

What is the Catholic Church in England and Wales for, exactly? Some might insist existence is enough and no more needs to be said. When the Catholic Church taught extra ecclesiam nulla salus without qualification, that was clearly an imperative. But the Catechism now states: “Those who, through no fault of their own, do not know the Gospel of Christ or his Church, but who nevertheless seek God with a sincere heart, and, moved by grace, try in their actions to do his will as they know it through the dictates of their conscience – those too may achieve eternal salvation” (quoting Lumen Gentium, 16). Paradise is open to all people of sincere goodwill. So why be Catholic? It is not a question that has yet been fully answered.

… Read more » … lire la suite »

WCC launches ‘Ten Commandments of Climate-Responsible Banking,’ encouraging faith communities to divest from fossil fuels

— Feb. 6, 20266 févr. 2026

The World Council of Churches (WCC) has released a new resource, Ten Commandments of Climate-Responsible Banking, calling on individuals, churches, and faith-based organizations to align their financial choices with climate justice and the wellbeing of future generations.

The guide stresses that money entrusted to banks is often invested in industries driving the climate crisis and urges believers to use their economic influence to support a transition away from fossil fuels and toward sustainable alternatives.

… Read more » … lire la suite »

Italy’s Christian churches sign first ecumenical pact

— Feb. 5, 20265 févr. 2026

Strengthening relations among different Christian churches in Italy, while promoting authentic Christian values within an increasingly secular society. Those were the twin goals of a recent symposium, during which representatives of eighteen churches and Christian communities signed an ecumenical pact pledging to pursue dialogue, joint witness and closer cooperation for the common good.

As dean of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Italy, Rev. Carsten Gerdes took part in the two-day symposium, held in the southern port city of Bari. The gathering included the signing of a bold new agreement between Catholic, Orthodox, Anglican, Protestant, Pentecostal and Free churches present around the Italian peninsula.

… Read more » … lire la suite »

Interfaith Harmony Week: Standing together against rising religious nationalism

— Feb. 3, 20263 févr. 2026

To mark the 1 to 7 February World Interfaith Harmony Week, LWF’s director for Theology, Mission and Justice reflects on the need to stand united against division and hatred, tending the flame of hope together.

When the United Nations launched the World Interfaith Harmony Week in 2010, the vision was for a week globally dedicated to highlighting common values across faith traditions, including all people of goodwill — love of God, love of the good, and love of neighbour. Sixteen years later, as we observe this week again, the onslaught of the unending bad news reminds me how the world has shifted dramatically. The challenge before us is no longer simply about dialogue and understanding. It’s about solidarity and cooperation for the common good in the face of rising religious nationalism globally.

… Read more » … lire la suite »

‘The Cross is our light’ – Christians pray for unity in Saskatoon at closing of week of prayer

— Jan. 30, 202630 janv. 2026

With prayer, song, reflection, and the symbolic sharing of the Light of Christ, Christians from many traditions gathered for the closing of the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity Jan. 25 at St. Andrew Presbyterian Church in Saskatoon.

Mary Nordick, chair of the Prairie Centre for Ecumenism, welcomed those gathered for the Sunday afternoon worship service, reflecting on the “blessed week” of prayer, events, and reflection from Jan. 18-25.

… Read more » … lire la suite »

Sarah Mullally confirmed as 106th archbishop of Canterbury

— Jan. 28, 202628 janv. 2026

Sarah Mullally was confirmed archbishop of Canterbury Jan. 28 at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, England. She became the first woman to hold the office in its 1,400-year history.

“It is an extraordinary and humbling privilege to have been called to be the 106th archbishop of Canterbury. In this country and around the world, Anglican churches bring healing and hope to their communities,” Mullally said ahead of her confirmation. “With God’s help, I will seek to guide Christ’s flock with calmness, consistency and compassion.”

… Read more » … lire la suite »